Like

many terms used to describe government structures, aristocracy

is impossible to define. Founded on the Greek word, aristos,

which means best, at its heart aristocracy means 'rule by the

best'. Its theoretical foundation begins with the political

works of Plato and Aristotle, the two central figures in Greek

and European philosophy. Both felt that Greek democracy had been

a disaster; their fundamental problem with democracy was that it

put government in the hands of people who were the least capable

of making sound decisions. For Plato, the general run of

humanity was driven by its selfish passions and desires; this

was a poor foundation for deliberate, considered, and selfless

decision-making. While Plato and Aristotle were familiar with an

infinite variety of possible governments, they believed that

government should be in the hands of the most capable members of

society. Above all, people in government should be moral and

selfless; they should be highly intelligent and educated, as

well as brave and temperate. This was 'rule by the best'.

This is not,

however, what we think of when we use the term aristocracy. In

early modern Europe and modern Europe, the aristocracy consisted

of the nobility or ruling classes of society. Membership in the

aristocracy was not through achievement, intelligence, or moral

growth, but solely hereditary (sometimes it was given out). How

did the Greek idea of 'rule by the best' turn into something

more closely resembling a hereditary oligarchy or just simply an

upper class?

The answer can

be found in part in theories of the monarchy in the Middle Ages.

In order to legitimate ta hereditary monarchy, the medieval

Europeans theorized that the virtues which made a monarch

suitable for the job were hereditary. This led to a

segregation of virtues: the monarch and his noble bureaucrats

were by nature and heredity more moral and civilized than the

rest of the population. They were, then, the 'best' morally and

intellectually. In this way, the notion of aristocracy, as 'rule

of the best', eventually translated into a concept of a

hereditary aristocracy. So ingrained is this notion in the

European world view, that we still assume a hereditary

superiority in the upper classes.

The founders of

American democracy turned back to the original, philosophical

definition of aristocracy when they built American government.

Very conscious of Plato's and Aristotle's criticisms of

democracy, the founders of American government wanted to avoid

putting the government into the hands of the worst members of

society. They also, however, wanted to avoid the dangers of a

hereditary aristocracy, for European history proven amply that

the hereditary aristocracy is many things but it rarely consists

of the 'best' members of society either in moral or intellectual

terms (look at the royal family in England, for instance). So

the framers of American government created representative

democracy, in which the people collectively decide who the

'best' people are to run the government. In this way, a limited

democracy is allowed to co-exist seamlessly with a government

that is primarily ruled by the most qualified people morally and

intellecturally, well, sometimes.

sir winston

leonard spencer churchill

Sir Winston Churchill was the eldest son of the

aristocrat Lord Randolph Churchill, born on 30th November 1874.

He is best known for his stubborness yet courageous leadership

as Prime Minister for Great Britain when he led the British

people from the brink of defeat during World War II.

Following

his graduation from the Royal Military College in Sandhurst he

was commissioned in the Forth Hussars in February 1895. As

a war correspondent he was captured during the Boer War. After

his escape he became a National Hero. Ten month later he was

elected as a member of the Conservative Party. In 1904 he joined

the Liberal Party where he became the president of the Board of

Trade.

It was in 1910

he became Home Secretary where he worked with David Lloyd George.

In 1911 he left the Home Office and became first Lord of the

Admiralty. His career was almost destroyed as a result of the

unsuccessful Gallipoli campaign during the First World War. He

was forced to resign from the Admiralty. However, he returned to

Government as the Minister of Munition in 1917. In this year he

joined the coalition party in which he was a member until it

collapsed in 1922 when for two years he was out of Parliament.

He returned to the conservative government in 1924 and was given

the job of Chancellor of the Exchequer. For ten years during the

depression Churchill was denied cabinet office. His backing and

support for King Edward VIII during his abdication were frowned

upon by the national government. However in September 1939, when

Nazi Germany declared war on Poland, the public supported him in

his views. Once again Neville Chamberlain appointed him First

Lord of the Admiralty on September 3rd, 1939.

In

1940 Churchill succeeded Chamberlain as prime minister and

during World War II he successfully secured military aid and

moral support from the United States. He travelled endlessly

during the war establishing close ties with leaders of other

nations and co-ordinated a military strategy which subsequently

ensured Hitler's defeat.

His

tireless efforts gained admiration from all over the world. He

was defeated however during the 1945 election by the Labour

party who ruled until 1951. Churchill regained his power in 1951

and lead Britain once again until 5th April 1955 when ill health

forced him to resign. He spent much of his latter years writing

(The History of the English-Speaking People) and painting. In

recognition of this historical studies he received the Nobel

Price for Literature in 1953 and in 1963 the US Congress

conferred on him honorary American citizenship.

In

1965, at the age of 90 he died of a stroke. His death marked the

end of an era in British History and he was given a state

funeral and was buried in St. Martin's Churchyard, Bladon,

Oxfordshire. During all of his life he had served no less than

six British monarchs: Queen Victoria, Edward VII, George IV,

Edward VIII, George VI and Elisabeth II.

democracy

The power of the

democratic idea has also evoked some of history's most profound

and moving expressions of human will and intellect, from

Pericles in ancient Athens to Vaclav Havel in the modern Czech

Republic, from Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence in

1776 to Andrei Sakharov's last speeches in 1989.

In the

dictionary definition, democracy is:

"...government

by the people in which the supreme power is vested in the people

and exercised directly by them or by their elected agents under

a free electoral system."

Freedom and

democracy are often used interchangeably, but the two are not

synonymous. Democracy is indeed a set of ideas and principles

about freedom, but it also consists of a set of practices and

procedures that have been molded through a long, often tortuous

history. In short, democracy is the institutionalization of

freedom. For this reason, it is possible to identify the

time-tested fundamentals of constitutional government, human

rights, and equality before the law that any society must

possess to be properly called democratic.

----------

Democracies

fall into two basic categories, direct and representative. In a

direct democracy, all citizens, without the intermediary of

elected or appointed officials, can participate in making public

decisions. Such a system is clearly only practical with

relatively small numbers of people, in a community organization

or tribal council, for example, or the local unit of a labor

union, where members can meet in a single room to discuss issues

and arrive at decisions by consensus or majority vote. Ancient

Athens, the world's first democracy, managed to practice direct

democracy with an assembly that may have numbered as many as

5,000 to 6,000 persons, perhaps the maximum number that can

physically gather in one place and practice direct democracy.

Today, the most

common form of democracy, whether for a town of 50,000 or

nations of 50 million, is representative democracy, in which

citizens elect officials to make political decisions, formulate

laws, and administer programs for the public good. In the name

of the people, such officials can deliberate on complex public

issues in a thoughtful and systematic manner that requires an

investment of time and energy that is often impractical for the

vast majority of private citizens.

liberalism

Liberalism

can be understood as a political tradition, a political

philosophy and as a general philosophical theory, encompassing a

theory of value, a conception of the person and a moral theory

as well as a political philosophy. As a political tradition

liberalism has varied in different countries. In England, in

many ways the birthplace of liberalism, the liberal tradition in

politics has centred on religious toleration, government by

consent, personal and, especially, economic freedom. In France

liberalism has been more closely associated with secularism and

democracy. In the United States liberals often combine a

devotion to personal liberty with an antipathy to capitalism,

while the liberalism of Australia tends to be much more

sympathetic to capitalism but often less enthusiastic about

civil liberties. To understand this diversity in political

traditions, we need to examine liberalism as a political theory

and as a general philosophy.

The Fundamental

Liberal Principle holds that restrictions on liberty must be

justified, and because he accepts this, we can understand Hobbes

as espousing a liberal political theory. But Hobbes is at best a

qualified liberal, for he also argues that drastic limitations

on liberty can be justified. Paradigmatic liberals such as Locke

not only advocate the Fundamental Liberal Principle, but also

maintain that justified limitations on liberty are fairly

modest. Only a limited government can be justified; indeed, the

basic task of government is to protect the equal liberty of

citizens. Thus John Rawls's first principle of justice: ‘Each

person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total

system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system

for all.

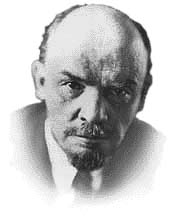

marxism-leninsim

A label of Lenin's

approach to Marxism at the beginning of the 20th-century, in a

capitalist Russia emerging from feudalism. While Lenin

considered himself only a Marxist, after his death his theory

and practice was given the label of Marxism-Leninism, considered

to be an overall evolution of Marxism in the 'era of the

proletarian revolution'. Marxism-Leninism was the official

political theory of the former Soviet state and was enforced

throughout most of the former Eastern European socialist

governments of the 20th-century.

The

creation and development of Marxism-Leninism can be divided into

two general categories: the creation and development by Stalin,

and the revision by Khrushchev and continual revisions by the

Soviet government to follow.

Stalin

defined Leninism in his work The Foundations of Leninism: "Leninism

is Marxism in the era of imperialism and the proletarian

revolution. To be more exact, Leninism is the theory and tactics

of the proletarian revolution in general, the theory and tactics

of the dictatorship of the proletariat in particular."

Stalin explained that Leninism first began in 1903, and was

identical to Bolshevism.

Stalin

explained that a foundation of Marxist-Leninist theory was that

a socialist revolution could only be accomplished by the

Communist Party of a particular nation, the vanguard of the

working class (its organizer and leader). After the socialist

revolution had been affected, this vanguard would act as the

sole representative of the working class.

While in some

ways a direct product of Lenin's philosophy for Russia,

Marxism-Leninism also took on new approaches. For example,

though Lenin believed that socialism could only exist on an

international scale, Marxism-Leninism supported Stalin's theory

of 'Socialism in One Country'. Stalin enforced Marxism-Leninism

as an international platform by explaining that its principles

and practices applied to the whole world.

In this way

Marxism-Leninism became the only true theory and practice of

Marxism in the 20th-century, 'without adhering to

Marxism-Leninism a socialist revolution could not be achieved'.

This assertion was partly based on one of the foundations of

dialectical materialist thinking: that practice is the criterion

of truth. Stalin explained that Lenin had shown through his

practice, a particular way to establish a socialist government

in Russia; thus that practice substantiated Lenin's theory as

true in Russia at the beginning of the 20th century. That

particular however, was extracted from its historical context

and converted into a universal. Hence the basis for why some

considered the label Marxist-Leninist to be partially idealist ,

because it placed the conditions of practice particular to

Russia at the beginning of the 20 century as true for all

countries in the world.

Despite

Stalin's creation and evolution of the Marxist Leninist

philosophy, the term was later used by the Soviet government in

support of 'De-Stalinification'. While Stalin had recognized the

theory of the Communist vanguard as a creation of Lenin, the

Soviet government headed by Khrushchev had explained that the

Communist vanguard was in fact a part of the 'Marxist' aspect of

Marxism-Leninism (an aspect which hitherto had been little

addressed). The Leninist aspect, Khrushchev explained, began in

the 'era of the proletarian revolution and socialist

construction'.

----------

Khrushchev

developed Marxism-Leninism to explain that a worldwide war

between workers and capitalists was no longer necessary, but

instead that the ideal of peaceful coexistence is inherent in

the class struggle. The new Soviet government further explained

that while Marxism-Leninism was created by the theory and

practice of the dictatorship of the proletariat (which Lenin had

explained as a short and transitionary form of government)

Marxism-Leninism evolved into the theory of a 'state of the

whole people' (This development was directly opposite of Marx,

Engels, and Lenin's theory of the state, that the state always

acts in the interests of a certain class, and when no classes

existed, the state would cease to exist).

After Lenin's

death, the creation, development and evolution of Marxism

Leninism was the focus of crippling sectarian battles throughout

the world over what Lenin 'had really meant'. Stalin explained

that the practice and understanding of Trotsky was completely

opposite of Leninism, while Trotsky criticized Stalin's

Marxism-Leninism as a failure. Mao criticized Khrushchev's

Marxism-Leninism as bourgeois revisionism, while Khrushchev and

later the Chinese government itself declared Mao a renegade to

Marxism-Leninism, etc, etc, etc.....

socialism

under construction...

trias

politica

under construction...